I recently talked about Target 3 of the new Global Biodiversity Framework – the so-called 30×30 target – and how much of the focus is on achieving the 30% protection target while forgetting the other important part of the target – how well-protected areas are managed.

I think there is perhaps a more nuanced discussion to be had around this whole target. Yes, the “30% of what?” question still has to be answered; but we also need to look at how we are managing protected areas – in the language of the framework, are they “effectively and equitably managed and governed”?

Focus limited resources on key biodiversity areas – and manage 30% of those

30% of what?

It feels like I have written that down so many times. So let’s finally look at the maths. Just how big is Malaysia’s marine estate?

The concept of an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) was introduced at the Third United Nations (UN) Conference on the Law of the Sea (1973–82) in order to settle potential disputes between countries by awarding sovereign jurisdiction within boundary waters to coastal states.

Exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as defined under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), describes an area of the ocean extending up to 200 nautical miles (370 km) immediately offshore from a country’s coast in which that country retains exclusive rights to the exploration and exploitation of natural resources.

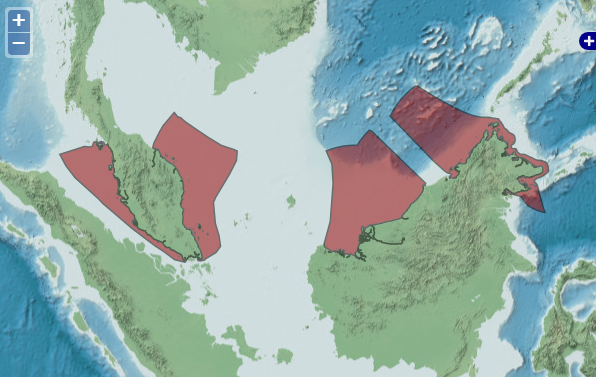

According to Wikipedia, Malaysia claims an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 334,671 km2, though confusingly different sources quote different figures. For example, the protected planet database indicates that Malaysia has a total marine and coastal area of 451,742 km2 (source: protectedplanet.com).

Sticking with the protected planet figure for now and looking at Target 3 literally, Malaysia would need to protect some 135,000 km2 of its marine area to meet the 30% target. However, protected planet states that Malaysia has 25,099 km2 of marine and coastal areas covered by MPAs, which is only 5.6% of marine and coastal areas. So…well short of the 30%.

EEZ is an area of the ocean extending up to 200 nautical miles (370 km) immediately offshore from a country’s coast in which that country retains exclusive rights to the exploration and exploitation of natural resources.

Key Biodiversity Areas

But the point I have raised before is that this numerical analysis ignores the reality on the ground.

An analysis of nautical charts of the East coast of Peninsular Malaysia suggests that much of the EEZ, beyond the immediate coastal area and the islands offshore, is actually a plain lying at around 50-60m or so deep. Neither charts nor Google Earth indicates any significant features such as seamounts within the EEZ area. For East Malaysia, the waters beyond the coastal area go much deeper – too deep for most marine ecosystems to thrive.

In both cases, it seems that marine ecosystems are limited throughout much of the EEZ area, when compared to the richness of coastal ecosystems such as mangroves, seagrass meadows and coral reefs. So the question has to be asked: why protect those areas?

Manage the fisheries, yes, but if there isn’t much habitat (or ecosystem) there to protect, then surely resources can be used more effectively in more important and productive high biodiversity areas?

So that’s the argument I am making: focus limited resources on key biodiversity areas – and manage 30% of those, which is a scientifically valid target.

Effectiveness and Equitable Management and Governance

But…what about effectiveness and equitable management and governance?

Let’s look at effectiveness first – because, if we aren’t managing our protected areas effectively, what’s the point in setting up new ones?

When people ask me what we do with the data from all the surveys we conduct, I try to explain how the data are useful for managers, who can see what is going on with marine ecosystems and, if there are signs of problems, take action to correct it.

“..focus limited resources on key biodiversity areas – and manage 30% of those, which is a scientifically valid target.”

However, the reality is that we know some things are going wrong, but we just aren’t taking the necessary steps to address the problems.

Between 2014 and 2019, our Annual Survey data showed a slow decline in reef health, as measured by what we call live coral cover. 1-2 percentage points per year…nothing much, right? But over 5 years, there was a reduction in live coral cover of 10 percentage points, which is significant. However, from 2019-2022 there was an improvement in reef health. This strongly indicates to us that the lack of tourists during the covid pandemic was a good thing for reefs!

So, we have data to show that tourism is bad for reefs – who’d have thought! But what have we done about the negative impacts tourism brings?

Improved sewage treatment on the islands? No.

Introduced limits on numbers of tourists? No.

Trained all tour guides to reduce physical damage to the ecosystems? No.

Filling in the gaps – we conduct eco-friendly snorkeling guide training with local guides

Don’t get me wrong: this is not about kicking the management agencies – they do a good job with limited resources. And, let’s face it, limited support; after all, protected areas can be unpopular with some stakeholders when they perceive that they lose access to traditional resources.

So, they are in a difficult position. Add to that the complicated jurisdictions involved, with numerous ministries, agencies and state governments involved, and you start to see how difficult it is to address management effectiveness.

No single person is responsible. Perhaps we need to address that weakness in the management system.

How does equity fit in?

And this is where we finally get round to equity. Equitable management and governance of protected areas means that all stakeholders are involved in management and decision making, particularly indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs).

Target 22 of the new biodiversity framework talks about ensuring the “full, equitable, inclusive, effective and gender-responsive representation and participation in decision making…by indigenous peoples and local communities”.

A friend of mine who works in the protected area field in Australia responded to an earlier post of mine on this issue, saying that:

“It’s critical that these protected areas are “effectively and equitably managed and governed” and that means managing them collaboratively with indigenous peoples and local communities. Australia is establishing more Indigenous Protected Areas over the sea. The Indigenous ranger teams that manage them combine cultural practices and contemporary conservation management techniques and where they’re well supported, he parks are well managed and are achieving conservation, social, cultural and economic goals.”

Australia is demonstrating that including local people leads to better conservation outcomes. And the great thing is, we know it works in Malaysia, too. Because we are already doing it.

On Tioman island, we have established the Tioman Marine Conservation Group (TMCG). We have trained 80 local islanders to conduct a variety of conservation programmes, including ghost net removal, coral predator management, restoration and monitoring surveys. They’re doing it for themselves, with funding from corporate partners.

TMCG member in action

Based on the success of the programme in Tioman, we are now replicating the programme on other islands, in the hope that we can achieve similar results there.

You can read all about what TMCG has been working on in 2022 here.

Reef Care – A Community-based Solution

And it gets better.

Community groups like the TMCG are now empowered by the Department of Fisheries’ Reef Care programme to get more involved. Reef Care was introduced in 2020 to give local communities living on the Marine Park islands some responsibility for managing “their” coral reefs. On Tioman island, TMCG is the local Reef Care partner (together with RCM) and the local community is playing an increasingly important role in helping to protect the marine resources around the island. We have found that islanders are becoming more engaged; attitudes to the Marine Park are more positive; reef health is improving – and the community benefits economically because they are paid to participate in TMCG programmes.

What’s not to like?

We hope to continue working with DoF over the next couple of years to expand the Reef Care programme to other islands and get more communities engaged. Hopefully, we will see improvements in reef health in these other areas, as we have seen in Tioman. Not to mention the benefits that come from greater participation and improved governance.