The 2010 paper “Defining Political Will” suggests that :

“Political will exist when a sufficient set of decision-makers with a common understanding of a particular problem on the formal agenda is committed to supporting a commonly perceived, potentially effective policy solution.”

Based on this definition, sufficient decision-makers refers to a sufficient number of people who are in positions of power who support the desired changes, agree that a particular issue has reached problem status, and that it requires government action.

These decision-makers must then be committed to the particular issue and reach a consensus on the type of policy response required.

Political will is complicated by the governance and institutional arrangements of the country. In our previous articles, we touched on some institutional and legal challenges that complicate managing our ocean resources. Ocean industries and coastal-based resource management (including conservation) are typically managed sectorally by multiple government authorities guided by exclusive policies, institutional arrangements, and legal instruments. This creates overlaps in jurisdiction and authorities; inconsistencies and gaps in legislative frameworks; amplifies multiple-use conflicts; increases duplication of efforts; creates unclear paths for stakeholders in pursuing interests and raises concerns on many uncoordinated approaches by different parties in similar issues.

A quick illustration is in the form of the National Policy on Biodiversity (NPBD). The policy is the responsibility of the Ministry of Water, Land and Natural Resources. However, the management of fisheries and marine protected areas are under the purview of the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industries, while maritime industries are managed by the Ministry of Transport.

This is further complicated by the inherently delicate relationship between the Federal and State governments. There are at least 32 key legislations (both Federal and State) concerning biodiversity conservation in Peninsular Malaysia; seven (7) in Sabah and eight (8) in Sarawak. These legislations are enforced by several authorities; each with its own objectives and coordination mechanisms.

A whole-of-government and society approach towards an adaptive National Ocean Policy

The Covid-19 pandemic has shown that large-scale urgent change is possible. The unprecedented level and speed of policy and legislative actions demonstrated our political will and capacity to adapt in the face of profound suffering and loss to our health, livelihoods, economies, and behaviours.

Reef Check Malaysia hopes that with the same determination, we can put in place a much-needed transformative change in the form of an adaptive National Ocean Policy supported by a dynamic form of governance to assist decision-makers and policy actors to address the gaps, harmonise initiatives and coordinate the actions of many government agencies that are typically involved in ocean affairs towards an agreed social and economic vision and common goals.

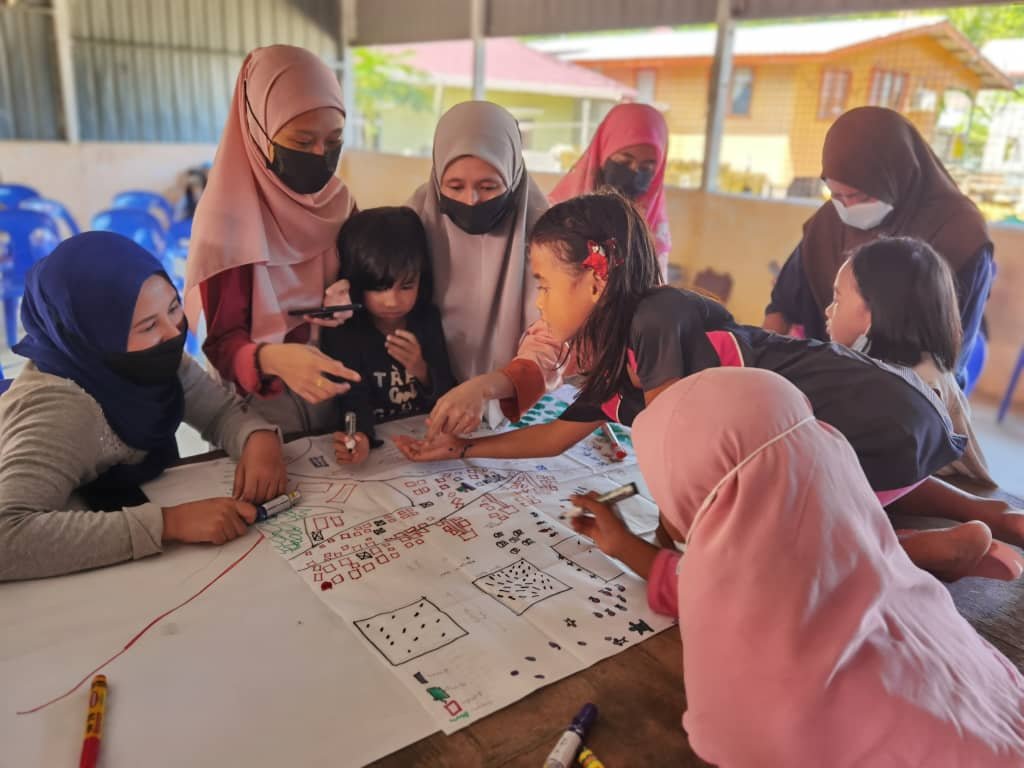

The development and implementation of such a policy hinges on all parties’ participation – from the adoption of a participatory approach with all concerned agencies and stakeholders to the determination and implementation of policy actions based on informed process, science and local knowledge.

As of 2015, 15 developed and developing nations had articulated and implemented an integrated, ecosystem-based ocean policy governing the ocean areas under their jurisdiction. This includes developing goals and procedures to harmonize existing uses and laws to foster sustainable development of ocean areas, protect biodiversity and vulnerable resources and ecosystems, and coordinate the actions of the many government agencies that are typically involved in oceans affairs.

Since then, countries such as Fiji (2020), Solomon Islands (2018), Indonesia (2017), and Vanuatu (2016) have developed their version of a National Ocean Policy.

In 2010, the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation commissioned the National Oceanographic Directorate to work on a draft Malaysia Ocean Policy.

The draft policy recommended guidance on national goals and principles that should govern our ocean and coastal activities. It also sets out recommendations to address the challenges of maintaining consistency in law and financial allocations in pursuit of the proposed defined goals. To achieve these goals, the draft NOP recommended that relevant existing laws and institutional arrangements will have to be harmonised in consideration of their cumulative impact on Malaysian ocean management. In essence, national laws will have to achieve integration to ensure their combined effectiveness in making certain that both current and future generations of Malaysians derive maximum benefit from the oceans.

Over the years, many individual experts and organisations have called for a revisit of the draft National Ocean Policy for Malaysia.

The revision should consider strengthening the existing recommendations that range from widening the reach of ocean-earth education, increase capacity building for all stakeholders, developing strategies for science and research & development, to remodel robust enforcement and monitoring measures that involve all parties including local communities.

Additional elements to the draft must embrace the development for sustainable financing; implementation of a blue and circular economy; mandatory reporting procedures; adequate enforcement of digital and technological advances in big data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and robotics as tools for problem-solving.

More importantly, improvements in the implementation of laws affecting ocean use and resources and related institutional strengthening must require a national ocean policy that is adaptive and has precise aims and objectives and is led by the highest office.

Retaining political will in Malaysia

Reef Check Malaysia is hopeful that, despite many political changes, Malaysia as a nation will steadfastly prioritise global common goals. In this case, prioritising our right to survive.

2021-2030 is the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development. This initiative gives member nations opportunities to seek solutions to reverse the cycle of decline in ocean health, and work with ocean stakeholders worldwide to move towards a common framework that will ensure ocean science can fully support countries in creating improved conditions for sustainable development of the Ocean. In this case, a framework for a National Ocean Policy.

This common framework shall be heavily influenced by the outcome of the upcoming 15th UN Biodiversity Conference (CBD COP15) this October in Kunming, China; and the 26th UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) in Glasgow from November 1-12, 2021.

However, all these efforts will come to nought if we fail to secure political leadership and commitment from respective parties.

Political differences and self-interest ought to be set aside as we face our biggest challenge yet, the survival and well-being of humanity.

#ecosystemrestoration #oceandecade #EarthDay2021 #oceanliteracy #oceanscience #malaysiaoceanpolicy #oceanpolicy