In my previous post, I talked about the recent signing of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, and tried to describe the treaty in its entirety. Now it’s time to look at some of the details – and how we implement the treaty.

That’s where the devil lies.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

In December 2022, Montreal, Canada, was the setting for the 15th Conference of Parties (COP 15) of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Presided over by China but held in Montreal (hence the name), the nations of the world finally agreed a package of measures to address what many scientists consider to be the dangerous loss of biodiversity that we are living through, not to mention the associated ecosystem services that biodiversity bestows upon society that we could not live without. Some even call it the “sixth great extinction” – the last one being 65.5 million years ago that saw the end of the dinosaurs…and nothing was ever the same again.

The vision of the framework is a world of living in harmony with nature where:

“By 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people.”

The mission of the framework for the period up to 2030, towards the 2050 vision is: To take urgent action to halt and reverse biodiversity loss to put nature on a path to recovery for the benefit of people and planet by conserving and sustainably using biodiversity, and ensuring the fair and equitable sharing of benefits from the use of genetic resources while providing the necessary means of implementation.

Profound words. But what do they mean in practice? The treaty has four goals and 23 targets, each of which will have indicators, means of verification, etc. But how do we go about implementing such a complex treaty – with topics ranging from protected area expansion through to financing mechanisms.

Let’s start with one target – perhaps the most divisive of them all – target 3, the so-called 30 by 30 target.

Target 3: 30x30

The first thing to note is…it’s long! In the original text, it runs to 8 lines…and it’s all one sentence! To simplify (and any errors in “interpretation” are mine alone), target 3 commits nations to:

Ensure and enable that by 2030 at least 30 percent of terrestrial, inland water, and of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services, are effectively conserved and managed.

This target has attracted international attention, with NGOs, civil society, academics and other institutions fiercely lobbying for the need to protect more of our natural areas, so as to conserve them in their native state and ensure we continue to benefit from those important ecosystem services. Such as food, clean water, climate regulation…

Just on the marine side, two global coalitions have formed to advocate for adopting this target:

The High Ambition Coalition (HAC) for Nature and People is an intergovernmental group of more than 100 countries co-chaired by Costa Rica and France and by the United Kingdom as Ocean co-chair. Its central goal is to protect at least 30 percent of the world’s land and ocean by 2030 with the aim of halting the accelerating loss of species and protecting vital ecosystems that are the source of our economic security.

The Global Ocean Alliance (GOA) is a 73-country strong alliance, led by the UK. It champions ambitious ocean action within the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). In particular, the GOA supports the target to protect at least 30% of the global ocean in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and Other Effective area-based Conservation Measures (OECMs) by 2030. This is known as the ’30 by 30 target’.

Remind me…30% of what?

If you have read my earlier posts you will already know that for a time during negotiations of the GBF there was a lack of clarity on just what the target meant. The timescale is clear – by 2030.

But… 30% of what?

Which ecosystems? Did it mean 30% of a participating country’s EEZ? Or 30% of the global oceans?

The 30% is scientifically justifiable: there are plenty of studies out there that suggest that protecting 30% of a particular ecosystem (or set of ecosystems) in a certain geographical area is a good idea (I’m not going to reference them all here…that’s what Google is for). One might call it prudent – like farmers used to put aside one-third of their land; let’s set aside a third of our ecosystems to protect them from harm, so they continue to supply those ecosystem services.

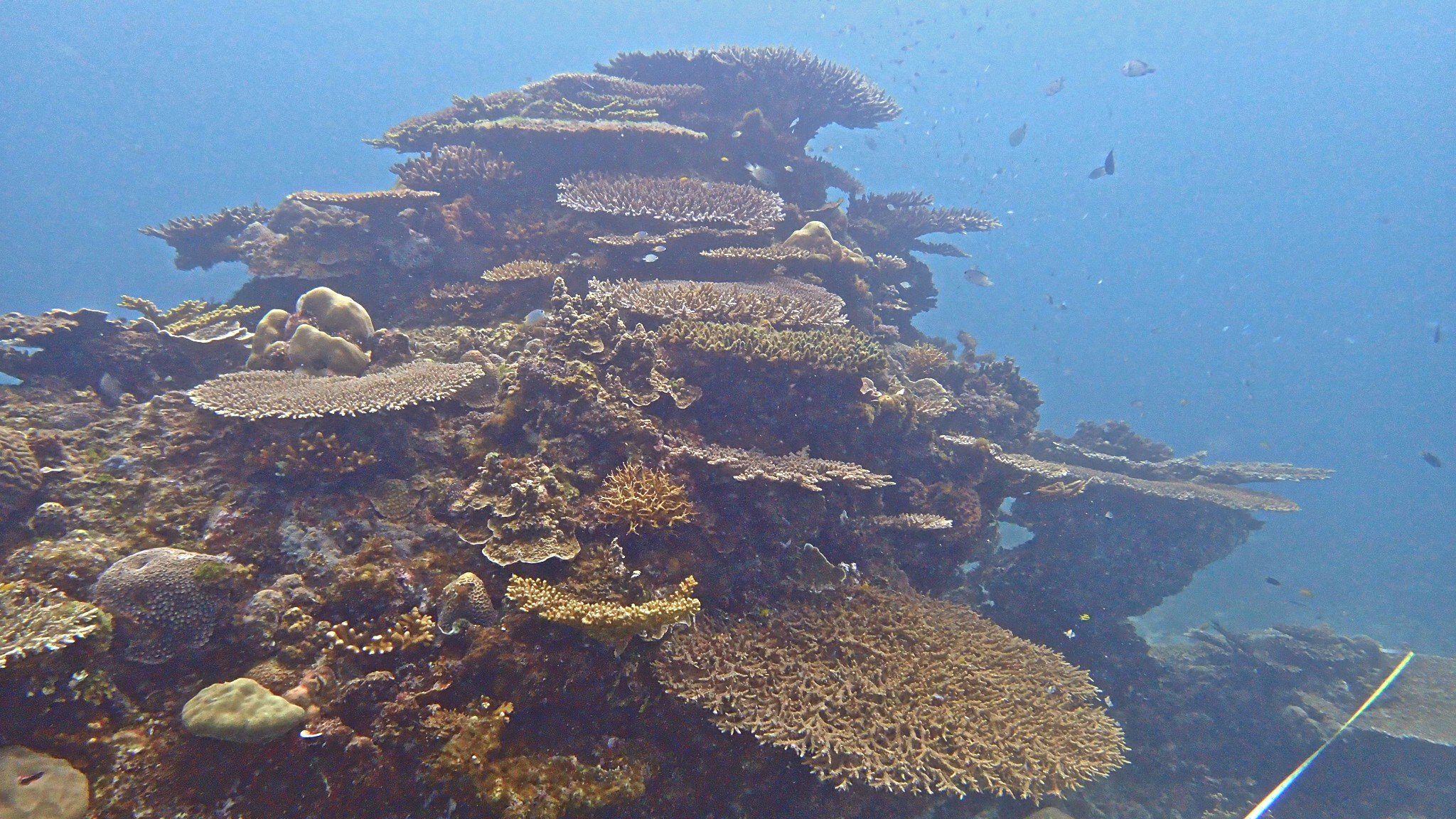

Imagine a cluster of islands off the East coast of Peninsular Malaysia. There are coastal mangroves, intertidal and tidal seagrass meadows, and coral reefs; all in a defined geographical area. Collectively they support community food security and livelihoods, as well as jobs in tourism, coastal protection, and so on. What the science says is that it is prudent to protect one-third of each of those three ecosystems. Hence, 30%.

What about the scope? 30% of what area, precisely?

In the end, it became clear that the intention of the target was to protect 30% of the global oceans, and that it is a “global ambition”, not a national target. Which is a good thing for Malaysia because as I have argued previously much of our EEZ doesn’t have much in the way of ecosystems, so how much protection should we afford those areas? Surely for a highly biodiverse country like Malaysia, with limited resources, the focus should be on the “areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem functions and services”.

And that’s how we arrived at our strategy to map the important coastal ecosystems and then identify which 30% we might want to protect, and then implement management systems to look after them.

30x30…the forgotten bit

And this is where – for me – we come to the crux of target 3. Because most people focus on the bit that talks about the area to protect – the 30%…and miss out on the incredibly important part of the target where it says “effectively conserved and managed...equitably governed…protected areas”. I’m paraphrasing, but that’s the gist of it.

Ah. There’s a thing in the conservation world called a “Paper Park” – the legislation is in place, the Park is accordingly recognised by the government, there’s a management agency…but somehow the protected area, or Park, isn’t managed well.

It exists purely on paper. And it is a problem throughout the world. Review the literature and one comes across all sorts of studies on this topic. I’m not saying all Parks are “Paper Parks”, I’m questioning whether we are achieving that important bit of the target: effectively and equitably managed and governed.

Establishing protected areas tends to be the preserve of national governments, or regional collaborations – or even international agreements. And, in most cases, governments are in charge of setting up their protected area estate.

So, it’s difficult for a small NGO like Reef Check Malaysia to talk about establishing Protected Areas ourselves – it’s just not realistic. But where organisations like us can make a difference is in helping to optimise how a Protected Area is managed.

Why?

Because we work with the communities living in these places and, I would be bold enough to suggest, perhaps understand their challenges and needs better than a bureaucratic organisation like a Protected Area management body – particularly if that body is geographically distant with limited local resources.

Full disclosure: we work closely with the managers of Malaysia’s Marine Parks (as they call MPAs here). In Peninsular Malaysia, that’s the Marine Parks Section of the Department of Fisheries; in the State of Sabah it’s Sabah Parks, and the Sarawak Forestry Corporation in the State of Sarawak.

We work with the communities living in the Protected Areas

We are also starting to work with management agencies at state level in Peninsular Malaysia (I know, it’s complicated!) including Terengganu, Johor and Perak. We have teams working on several islands – both inside and outside Marine Parks. This is not intended to be a criticism of those agencies – quite the opposite: given the size of the challenges they face; they’re doing a good job.

But…things could be better.

Every year we survey over 200 coral reef sites around Malaysia (reports are available on-line at www.reefcheck.org.my). Our data over the last few years show a gradual decline in reef health across Malaysia. Local impacts such as marine tourism, coastal development, pollution from sewage and other run-off are all damaging these critical ecosystems

So: this is a plea to strengthen the management of these important ecosystems. And more importantly – to recognise and involve an important stakeholder that has largely been side lined to date – the local communities on the islands. These so called “IPLCs” (Indigenous People and Local Communities) have been strongly recognised by the new treaty, and they are taking a more central role in management.

Next: how to make this actually happen!